GainSeeker

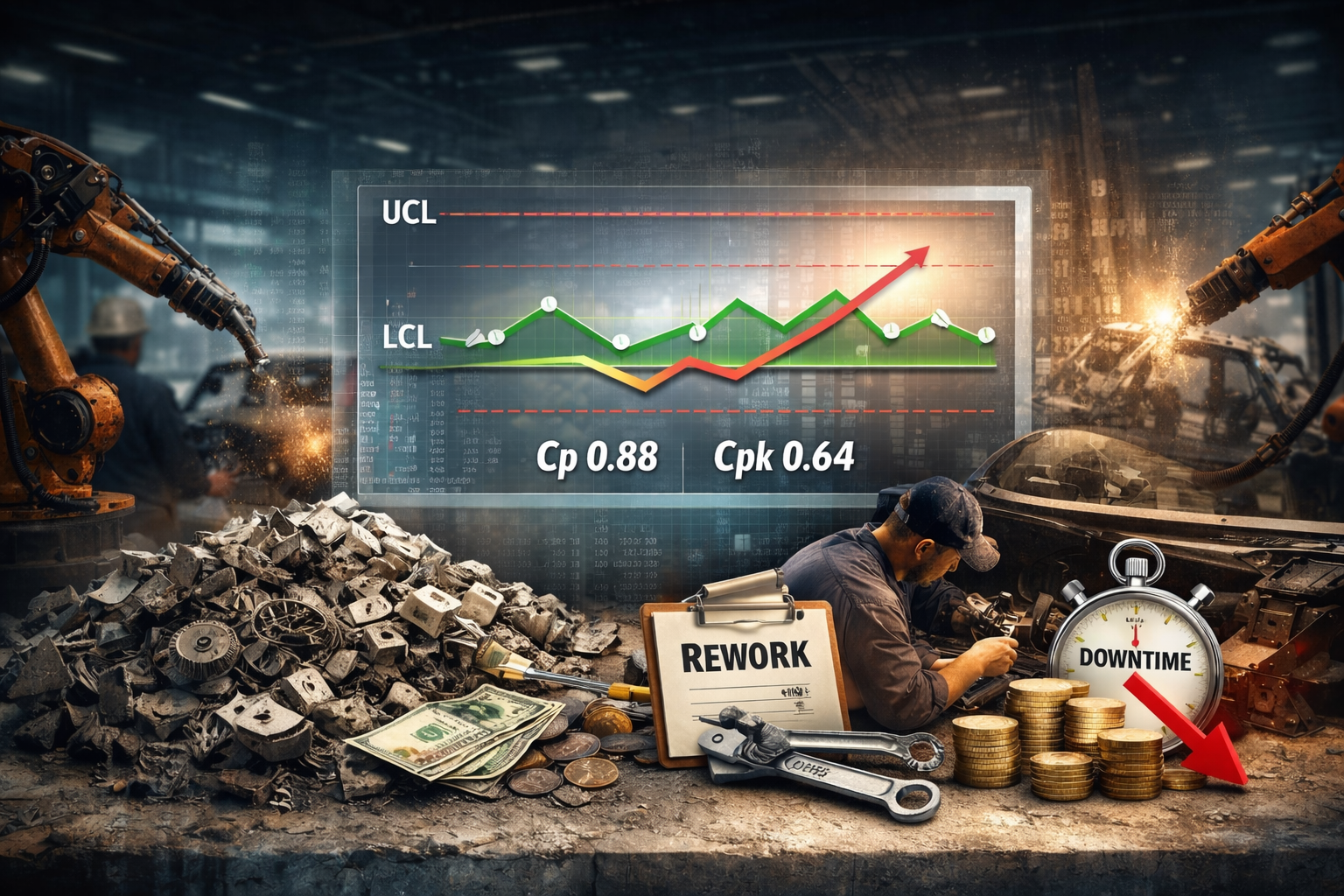

Most automotive manufacturers do not lack Statistical Process Control.They have control charts.They track Cp and Cpk.They collect large volumes of quality data across machining, assembly, and finishing operations.Yet scrap, rework, and unplanned downtime continue to erode margins.This is the central contradiction facing automotive manufacturing as it moves into 2026. The issue is not whether manufacturers understand SPC fundamentals. The issue is that SPC is too often treated as a reporting requirement instead of a system for managing process capability. When SPC data does not drive timely decisions, process instability persists, defects escape downstream, and costs accumulate quietly.This article examines SPC in automotive manufacturing from a performance and cost perspective, not a fundamentals one. It explains why SPC frequently fails to reduce scrap and downtime, what that failure truly costs, and how high-performing manufacturers-including Toyota-use SPC to achieve measurable financial results.

Automotive manufacturers continue to read about SPC for a simple reason: they are paying for instability they already know exists.

Most quality and operations leaders understand variation, control limits, and capability indices. What remains elusive is not SPC knowledge, but consistent results. Scrap, rework, and downtime persist—even in plants with mature quality systems.

As material costs rise, labor availability tightens, and customer expectations continue to increase, the margin for inefficiency has disappeared. Small process shifts that once felt manageable now translate directly into missed delivery targets, capacity loss, and financial exposure.

The question facing automotive manufacturers is no longer whether SPC is valuable. It is why, despite widespread adoption, SPC so often fails to deliver sustained process stability and cost reduction.

Process instability creates multiple cost streams simultaneously. Scrap, rework, downtime, excess inspection, and lost throughput all stem from uncontrolled variation.

Industry data consistently shows that the cost of poor quality (COPQ) in manufacturing ranges from 15% to 30% of total operating costs when all factors are considered. In automotive environments operating at scale, these costs escalate quickly.

A common scenario looks like this:

A machining process begins to drift. Parts remain technically within specification, but variation increases. SPC charts are updated, but no action is taken because no control limits are violated. Days or weeks later, defects appear downstream.

At that point, costs multiply:

Cost Category

Financial Impact

Scrap material

Lost raw material and machine time

Rework labor

Additional handling and processing

Downtime

Line stoppages during investigation

Capacity loss

Reduced throughput

Customer risk

Late shipments or escapes

What could have been a minor adjustment becomes a six- or seven-figure problem.

This is why SPC must function as a risk-reduction system, not a documentation exercise.

SPC fails when it is disconnected from decision-making. Many manufacturers are familiar with the benefits outlined in resources like

Benefits of Statistical Process Control (SPC) for Manufacturing Companies.

The challenge is not knowing SPC is valuable. The challenge is using it consistently and correctly.

Failure Mode

What Happens

Compliance-driven SPC

Charts exist to satisfy audits

Delayed review

Data is reviewed after defects occur

No response plans

Teams hesitate or over-adjust

“In-spec” mindset

Growing variation is ignored

When SPC exists primarily to meet customer or audit requirements, it does not prevent scrap—it records it.

When SPC is used correctly, it directly supports cost reduction.

High-performing automotive manufacturers use SPC to answer specific operational questions:

Organizations that treat SPC as an active management system commonly achieve:

Performance Area

Typical Improvement

Scrap reduction

30–50%

Process capability

Sustained Cpk improvement

Downtime

Fewer unplanned stoppages

Annual savings

Often measured in millions

These results come from acting on variation early, not from collecting more data.

Control charts only create value when they trigger action.

Automotive manufacturers routinely use:

The issue is rarely chart selection. The issue is what happens—or does not happen—when a signal appears.

SPC Element

Purpose

Defined signals

Identify meaningful process changes

Clear ownership

Ensure fast response

Standard actions

Avoid trial-and-error

Knowledge capture

Prevent repeat issues

Without these elements, control charts become historical records instead of real-time decision tools.

Scrap and rework are not unavoidable; they are indicators of unstable processes.

Every scrapped part represents:

SPC reduces scrap and rework by identifying variation before defects are produced. Instead of reacting at final inspection, teams intervene at the process level.

This approach aligns directly with proven strategies outlined in

How to Reduce Scrap and Rework in Manufacturing.

Manufacturers that use SPC proactively do not just reduce scrap—they stabilize processes so waste does not return.

Process instability is a leading cause of unplanned downtime.

Unstable processes create:

By stabilizing processes, SPC reduces reactive interventions. When variation is controlled, production becomes predictable and uptime improves.

This relationship is explored further about How to Reduce Downtime in Manufacturing.

Quality stability and operational uptime are not separate goals—they are directly connected.

Automotive manufacturers that consistently reduce scrap, rework, and downtime do not rely on more SPC data—they rely on better SPC execution.

These organizations focus first on the processes with the highest financial and operational risk. They define clear response plans for SPC signals, assign ownership for action, and train teams to interpret variation before defects occur.

Most importantly, they treat SPC as a management system rather than a quality tool. SPC signals are tied directly to production decisions, maintenance actions, and escalation protocols.

The result is not just improved charts, but more stable processes, predictable throughput, and measurable cost reduction.

Automotive manufacturers do not struggle with SPC because they lack data, charts, or capability metrics. They struggle because SPC is rarely implemented as a complete operating system.

Getting SPC “right” means more than tracking variation. It requires clear ownership, defined response plans, disciplined execution, and a direct connection between process behavior and business outcomes.

This is where Hertzler’s GS Premier makes the difference.

GS Premier is designed to close the gap between SPC theory and day-to-day execution. It transforms SPC from a reporting activity into a managed system—one that detects risk early, drives consistent response, and prevents small process shifts from becoming expensive failures.

When SPC is embedded this way, scrap and rework fall, downtime becomes predictable instead of reactive, and process stability stops being an aspiration and becomes standard practice.

For automotive manufacturers looking to finally align SPC with cost, performance, and operational control, GS Premier is the framework that makes it possible.

Reviewed by Phil Mason, MBA (Janurary 2026): Phil has been the VP of Business Development at Hertzler Systems Inc. since January 2010. Previously, Phil was an Adjunct Professor at Green Mountain College (until Jun 2018), Associate Professor at Goshen College, Executive Director Adult/Graduate Programs at Goshen College (Jul 2015-Dec 2016), Assistant Professor at Bethel College (from Aug 2011), Business Development at Digitec, Inc. (Oct 2008-Nov 2010), Regional VP at Mennonite Mutual Aid (Sep 2001-Feb 2008), and General Manager at Ikon Technology Services (from Jan 1999).

Links: LinkedIn Quality Magazine FinalScout